Volume 31, Issue 4, 2020

Volume 31, Issue 4 2020

Dr Tim Crowe, Nutrition researcher and educator

Never in the history of humankind have we had a more abundant, healthy and nutritious food supply as we do today in the Western world. But with that abundance comes all manner of foods designed to appeal to our sense of taste and desire for convenience. This is the domain of ultra-processed foods which are now recognised for the unhealthy addition they make to our diet.

Figure 1: Ultra-processed foods dominate diets in the Western world.

It’s an easy throw-away line on social media that the key to good health and nutrition is to ‘Just cut out processed food’. But such advice shows naivety for what happens to food in the journey to our plate. The term ‘processed food’ may seem like a dietary demon that we need to avoid, but it is a concept that has little meaning and is unhelpful in informing food choices.

Almost everything you eat is processed to an extent. Even cooking food is a form of food processing. Unless you are eating only fresh fruits and raw vegetables, raw eggs and maybe raw fish and meat, there is little in our diet that could be described as truly ‘unprocessed’.

A much more helpful concept is to divide food into categories based on their degree of processing. So, think more of food that has been minimally processed and is still close to its natural state in appearance and nutritional quality. Here it is all about fruits vegetables, fruits, wholegrains, nuts, milk, fresh meats and legumes. The sorts of foods featured in dietary guidelines. And against that, we have the foods we should be most concerned about: ultra-processed foods.

Nutrition science is now defining the processed foods we should be most concerned about. Ultra-processed foods are industrial formulations of food-derived substances that contain little if any whole food. Ultra-processed foods often include ingredients not commonly used in home cooking such as flavourings, colourings, emulsifiers and other additives. A key feature of ultra-processed foods is that they are usually appetising and pleasing to the taste buds, convenient, sold in large packages and highly marketed.

The category of ultra-processed foods emerged from an attempt to classify food by its level of processing by the NOVA food classification system. NOVA is a system of food organisation created by a team of nutrition and health researchers at the University of São Paulo. It is now recognised by global health agencies including the United Nation Food and Agriculture Organisation and used by many researchers globally.

NOVA categorises food products by the extent and purpose of food processing as a proxy for the food’s nutritional and environmental characteristics. The NOVA system clusters food into four groups. Table 1 outlines the different NOVA food categories.

Ultra-processed food refers to a specific group in the NOVA system. These are industrially processed foods that tend to be energy dense and high in fat, salt, sugar and additives, while typically being low in dietary fibre and micronutrients. What sets ultra-processed foods apart from other foods is the extent and purpose of processing. Ultra-processed foods have a higher level of processing that changes the food and often stimulates overconsumption.

Table 1. The NOVA Food Classification System

| NOVA Food Grouping | Examples |

|---|---|

| Group 1: Unprocessed and minimally processed food Characteristics: Minimal processing may include drying, pasteurisation, cooking and chilling | Fruits, vegetables, nuts, meat, eggs, milk, legumes, pasta, wholegrains and rice |

| Group 2: Processed culinary ingredients Characteristics: Undergo some processing to make products that can be used in cooking Group 1 foods but are not meant to be consumed by themselves | Oils, butter, sugar and salt |

| Group 3: Processed foods Characteristics: Usually made from two or three ingredients.Usually made by Group 2 substances added to natural or minimally processed foods (Group 1) to preserve or to make them more palatable | Preserved fruits and vegetables, canned fish, cured meat, cheese, fresh bread, beer and wine |

| Group 4: Ultra-processed foods Characteristics: Contain little, if any, intact Group 1 foods.These foods go through multiple industrial processes (such as extrusion, pre-prying milling) and contain many added ingredients with usually at least five or more ingredients.Colours, flavours, emulsifiers and other additives are often added to make products more palatable | Soft drinks, sweet/ salty/fatty packaged snacks, confectionery, mass-produced breads/ baked goods, cake mix, margarine and other spreads, sweetened breakfast cereals, pre-prepared meat, chicken ‘nuggets’, burgers, instant soups, packaged desserts, energy bars, baby formula and meal replacements |

Ultra-processed foods are designed to be appealing, convenient to consume and palatable so are more likely to displace the consumption of healthier, less processed foods. The convenience of ultra-processed foods can mean people may choose them over foods that are healthier, but which require more preparation time and effort. A diet high in ultra-processed foods can mean people lose their skills and interest in making healthy dishes for themselves. Ultra-processed foods also produce higher profit margins for food companies which helps fuel big marketing budgets, further competing out interest in less processed foods by the consumer.

Ultra-processed foods are a big problem in the Australian diet, contributing to over 40 percent of Australians’ daily energy intake. These foods are also key drivers of excessive sugar intake among all age groups. So, you can see how much of a problem eating too many of these foods can be.

Ultra-processed foods are are over-represented in the list of discretionary food choices that form part of the Australian Dietary Guidelines. Such foods are not an essential part of a nutritious diet. Now nutrition health professional around the world are identifying these foods as a major driver of overweight and obesity, and as contributors to non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes and certain cancers.

A diet high in ultra-processed food is linked to a greater chance of weight gain when eaten over the long term. A recent study that tracked more than 6,000 adults in the United Kingdom found that over eight years, people with diets high in ultra-processed foods were more likely to be heavier and had almost double the chance of becoming obese compared to people who ate the least ultra-processed foods. The more ultra-processed food a person ate, the greater their chance of becoming obese. For every 10 percent increase in the consumption of ultra-processed foods, the chance of being obese rose by a disproportional 18 percent.

Then there was a recent study from Spain spanning more than seven years which also found a link between ultra-processed food consumption and health. A higher consumption of ultra-processed food, to the extent it made up a third of a person’s diet, was associated with a higher risk of dying at a younger age. This is likely explained by the link between poor diet and chronic diseases such as obesity, heart disease, type 2 diabetes and some cancers.

Scientists are now looking deeper into what may be so insidious about ultra-processed foods that link them to weight gain. In a small, but important, study, 20 people in a controlled inpatient environment spent two weeks eating either a highly processed or unprocessed diet. They then spent the following two weeks eating the opposite diet. While the degree of processing between the diets was very different, the kilojoules, sugar, fat, fibre and many other nutrients were identical. It was only when people were eating the highly processed food diet that they gained weight – almost one kilogram in the two weeks. And this weight gain was entirely explained by them eating a greater volume of food. Why did they eat more food? It seems they tended to eat faster – potentially not allowing enough time for their body to signal to their brain that they were full.

The NOVA classification system of ultra-processed food is not a perfect guide and it does have its critics. Not all foods in the ultra-processed category need to be shunned as some of them can play an important role in providing nutrition. Infant formula is one example. And while there are many poor choices on the market, some breakfast cereals are a good source of convenient nutrition. This is not surprising as NOVA classifies foods based on the extent and purpose of food processing, not by their nutritional merits.

As a concept though, grouping foods according to their degree of processing can be a useful guide to their likely effect on health. So, at a public health and policy level, it’s a useful tool to help guide consumer food choices, inform food labelling changes and allow industry to work transparently in reformulating food in healthier and less processed ways.

The NOVA classification system is seeing a lot of use by nutrition researchers and international organisations, although it is unlikely you will find anything related to it on food packaging in Australia any time soon. However, with a bit of knowledge, you can apply the principles of NOVA to see which category a food would fit into. This is where becoming a food label reader pays dividends especially as most ultra-processed foods come in packaging that needs labels.

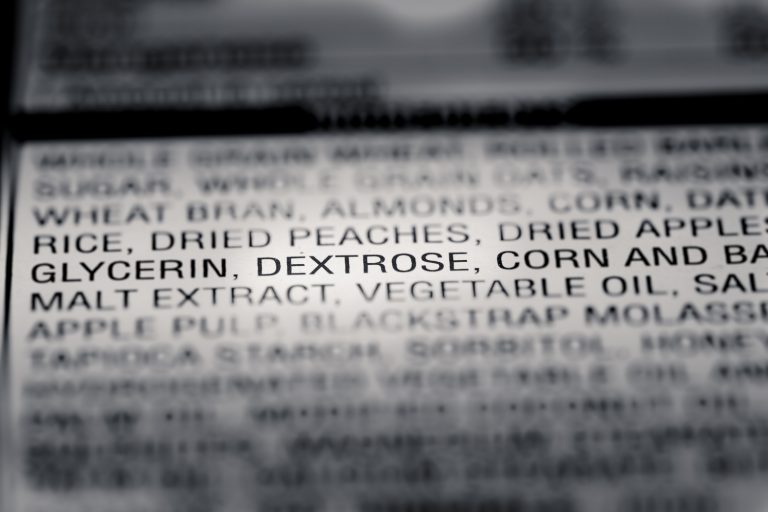

Look at the ingredients list of the food and ask yourself if all these ingredients would likely be found in a home kitchen? If the ingredient list is long, and many of the items don’t sound like food you would buy off the supermarket shelf, that is a strong hint that you are looking at an ultra-processed food.

Figure 4: Ingredients lists can offer a clue as to how highly processed a food is – if it has a long list of ingredients that you don’t recognise, it is likely to be ultra-processed.

Most of the food we eat is processed to some degree. But it is only the foods considered to be ultra-processed that we should aim to eat less of. Eating food as close to its natural state as possible, making food from original ingredients and choosing a wide variety of mostly plant-based foods are the keys to eating a healthy diet.

1. Name three foods that you regularly eat that could truly be called ‘unprocessed’

2. List some examples of minimally processed foods

3. What is the nova working definition of ultra-processed foods? Give some examples of ultra-processed foods

4. What makes ultra-processed food so appealing to consumers?

5. Outline the evidence that links eating too many ultra-processed foods to weight gain.

6. What is one likely reason to explain why eating too much ultra-processed food could cause weight gain?

7. What are some valid criticisms of the nova food classification system?

8. Look at the food package labels of a range of foods that you have in your home.What proportion of these foods would be considered ultra-processed?

Australian Dietary Guidelines https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/guidelines

Blanco-Rojo, R.et al.2019, ‘Consumption of ultra-processed foods and mortality: a national prospective cohort in Spain’, Mayo Clinic Proceedings, vol.94, no.11, Nov., pp.2178-88.

Hall, K.et al.2019, ‘Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake’, Cell, vol.30, no.1, Jul., pp.67-77.

Machado, P.P.et al.2019, ‘Ultra-processed food consumption drives excessive free sugar intake among all age groups in Australia’, Europen Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Nov., doi: 10.1007/s00394-019-02125-y.

Rauber, F.et al.2020, ‘Ultra-processed food consumption and indicators of obesity in the United Kingdom population (2008-2016)’, PLOS ONE, vol.15, May, e0232676.